Nobuyoshi Araki - Japan’s Most Notorious Photographer

- PleaseKnock

- Dec 9, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: Feb 26, 2023

Born in Tokyo, Japan, in 1940, prolific photographer Nobuyoshi Araki got his first camera at age 12, a gift from his father. After graduating in photography and film at Chiba University in 1963, he worked as a commercial photographer at Dentsu, later describing his work as his "training era". Much of it was dull. And that's ok because Araki's theme is to record the everyday, his work serving as a visual diary to all the messy, fast, mundane contradictory, complex inexplicable bits that make up a busy life. The singer Bjork, whom Araki photographed for the cover of her 1997 remixes album Telegram, called him "the most energetic man I know".

His graduation film Children in Apartment Blocks gave Araki the idea for his first photographic work, Satchin (1964), which focussed on school children during the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Young school children making sense of their world as something momentous and historic was happening around them paralleled Araki's different experience as a child when nuclear weapons devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

At Dentsu, he experimented, making handmade photo books by pasting prints directly into a sketchbook, In 1970 he created and self-published the multi-volume Xeroxed Photo Albums - "for learning (masturbation) and self-propagation (Gaijutsusakyo)" - apparently named after the company photocopier on which he reproduced his images of people, things and the suff around him. Designed in limited editions and sent to friends, art critics and, as legend has it, people selected randomly from the telephone book, the pictures offer an unabashed look at his private life, sexual and otherwise.

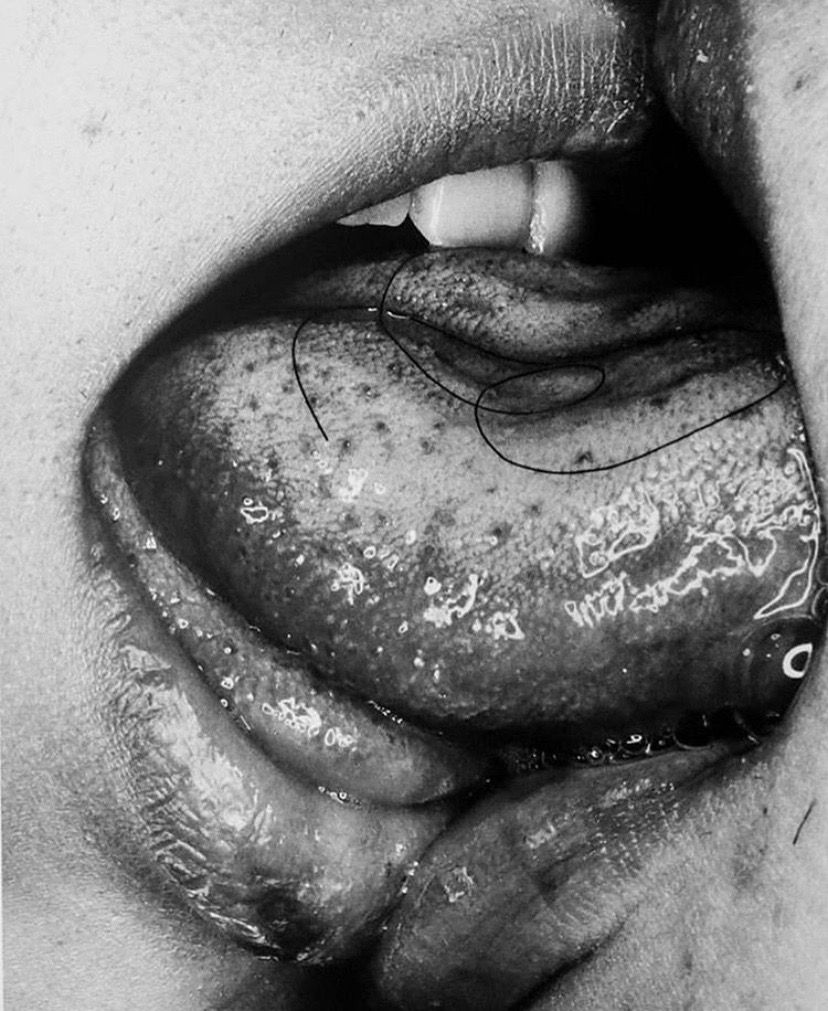

Ah, yes, the sex. It's not all sex with Araki, but when he gets down to it, it tends to hog the headlines. Araki has dubbed his work “I-photography”, after the “I-novel”, a Japanese literary genre often written in the first person. Others might call it 'I-pornography' and wonder if the images of women contorted in bondage and hooked to the ceiling qualifies as art. But, then, why can't porn be art, and vice versa? "I'd like to take photos similar to Shunga," he once said, referencing the popular erotic art style that reached its height in the Edo period (1603 to 1867) and of which Araki is a fan, "but I haven't reached that level yet. There is bashfulness in Shunga. The genitals are visible, but the rest is hidden by the kimono. In other words, they don't show everything. They are hiding a secret."

And when secrets are exposed, they die. Diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2008, Araki used his diagnosis to comment on the finite life of analog photography. For the 2009 series 2THESKY, he covered his photographs with salt, which will cause the object to deteriorate over time, reflecting the physical decline of the photographer himself.

His first major project, Sentimental Journey (1971), documented his honeymoon with Yōko. This was an explicit and revealing series of photographs depicting all aspects of the couples' life. Yōko was Araki's muse. She was, he claimed, the reason he became a photographer. He documented their life together and most poignantly the events leading up to her death from ovarian cancer in 1990's Winter Journey.

The nuance of Winter Journey contrasted starkly with Akari's exploration of the Shinjuku sex trade during the 1980's in Tokyo Lucky Hole, which was published the same year. Tokyo Lucky Hole presented images of naked women with a black circle covering their genitalia. Araki pushed against this type of censorship in his later work, placing a flower, or sometimes a toy, or jewellery over or in a woman's genitals, suggesting here is the source of all life and creativity. Men are cast as toy plastic dinosaurs to be used or discarded.

Contextualized in relation to Japan's history of Shunga, traditional erotic woodblock prints, and Kinbaku-bi, a style of Japanese rope bondage, Araki’s work is a new take on the country's attitude to sex. Nobuyoshi Araki's intimate shots of women, often in captivating black and white monochrome, are both provocative and insightful. Pictures of trussed-up women in various states of undress explores the hidden eroticism beneath Japan's conservative society.

Since Yōko's death, Araki's photographic output increased dramatically. By some estimates, he has published over 500 photographic books. Just under half are erotica, the rest documentary, street photography, and nature (flowers, fruits, animals). Now blind in one eye, a survivor of prostate cancer, photography is Araki's manna of life.

“It is a way of life. Taking photographs is like heartbeat and breathing. The sound of pressing the shutter is like a heartbeat. I don’t think about productivity at all. I just shoot life itself. It is very natural for me.”

“I needed to break down the me-and-you barrier. I can say that I have collapsed the previous tradition of photography that emphasized objectivity. In the past, photographers felt they had to eliminate their subjectivity as much as possible. I consider myself a “subjective” photographer. I try to get as close as possible to the subject by putting myself within the frame. In addition, this action avoids making my photographs mere works of art. Photographs taken by others are better photos than I took [ laughs]. Sometimes I give my camera to a subject and my subject takes a picture of me.”

“Photography is lying, and I am a liar by nature. Anything in front of you, except a real object, is fake. Photographers might consider how to express their love through photography, but those photographs are “fake love.” That is how I make the future and past."

"Women? Well, they are gods. They will always fascinate me. As for rope, I always have it with me. Even when I forget my film, the rope is always in my bag. Since I can't tie their hearts up, I tie their bodies up instead."

“For a photographer, the moment he shoots is most thrilling. Developing and printing comes later; it is secondary. That’s why we are all poor. I enjoy taking pictures very much, but I am not thinking about the rest.”

“It must be kami (god). What makes a photographer take a picture? What makes an artist paint a picture? It can’t really be explained. It’s a kind of instinct or impulse.”

“In general, the most challenging aspect of photography is taking pictures without any prejudice. As I am taking pictures, I am so engrossed that I do not think of anything else – like how to take pictures, which technique I should use etc. The mere act of taking pictures, this is the most exciting thing to me.”

"In the act of love, as in photography, there is a form of life and a kind of slow death."

“I’m trying to catch the soul of the person I’m shooting. The soul is everything. That’s why all women are beautiful to me, no matter what they look like or how their bodies have aged.”

"The camera itself, the photograph itself, calls up death."

Comments